Today on the blog, I’m reviewing a book I read all the way back in June and am so excited to be able to talk about more!

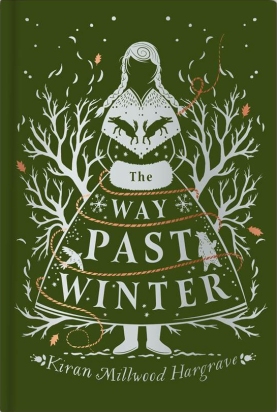

Author(s): Kiran Millwood Hargrave

Author(s): Kiran Millwood Hargrave

Publisher: Chicken House Books

Publication date: 4th October 2018

Source: I received an advance copy of this book in exchange for an honest review. Any quotes taken from this copy may be subject to changes in final editions.

Find on Goodreads and The Book Depository

Mila and her sisters live with their brother Oskar in a small forest cabin in the snow.

One night, a fur-clad stranger arrives seeking shelter for himself and his men. But by the next morning, they’ve gone – and it looks like Oskar has joined them. Twelve-year-old Mila can’t believe her beloved Oskar would abandon them. But then she never believed her father would abandon them either, and he disappeared years ago.

Then she learns that all the boys in the village have gone. Except one – an outcast mage called Rune. To discover the truth, Mila and Rune set out in a dog sleigh to find Oskar and bring him back. Even if it means facing a wilderness full of dangerous, magical things. Even if it means going all the way to the frozen north…

Kiran Millwood Hargrave is having a bit of a moment. Already a published poet and playwright when her first children’s novel The Girl of Ink and Stars was picked up by Chicken House Books, it was shortlisted for the Branford Boase Award, declared Children’s Book of the Year at the British Book Awards and won the Waterstones Children’s Book Prize. Her second children’s book, The Island at the End of Everything, was shortlisted for a Blue Peter Book Award and the Costa. The first book in a feminist YA series, Bellatrix, which will see her working with fellow Costa nominee Kit de Waal, is slated for July 2019. A buzzy 13-way auction for rights to her first adult novel The Mercies (previously known as Vardø) earlier this year was eventually won by Picador, with publication set for 2020.

What, then, of The Way Past Winter, which seems to bridge a critical moment between Millwood Hargrave’s children’s fiction and a transition to work for older audiences? Has this relatively short adventure been left in the dust in the rush to get to other projects? It certainly seems like a break with tradition when compared to The Girl of Ink and Stars and The Island at the End of Everything, which both feature long titles, only children, and sun-drenched tropical island settings. The characteristic girl heroine and male villain remain, and islands are to an extent still places of wonder for this writer, but the trading of sand for snow and sun for ice has the effect of conjuring a world as fresh and sharp as the air after a storm. It seems that Millwood Hargrave has found the means to step further away from the formula set by her first book – and her plunge into this wintry landscape is often brilliant.

Mila’s quest to find her brother is one of snowy forests and eerie mountain cities, breakneck chases and perilous encounters, fierce creatures and mesmerising wilderness. As their close-knit sibling group splinters and older sister Sanna concludes that Oskar was desperate to take any opportunity to abandon them – perhaps an expression of her own frustrated longing to see the world beyond the forest – Mila is sure there’s something more to his disappearance. She is joined in her search by mysterious boy-mage Rune, bright-eyed younger sister Pípa, and loyal canine companions Dusha and Danya. Theirs is a world which awaits a far-off spring; one of superstition and stories, like that of Bjorn, bear protector of the forest. I would’ve liked slightly deeper exploration of certain plot threads or secondary characters, but on the whole, simple devices are woven into an effective, engrossing adventure.

It is not unexpected that nature should prove fruitful literary ground here (“Cold hovered like a carrion bird”; “it was the way of the mountains to carry on outdoing each other”), or that there are poetic influences (“A dark fizzing, like a hot coal spitting”). More important is that Millwood Hargrave is hitting her prose stride. The Way Past Winter features a compelling goal, exciting action and well-defined structure. Some of my favourite lines were character-centric (“Oskar had grown up so fast it seemed he had left loving them behind”; “She felt empty, like a hand that is dropped when it is used to being held”), but some came even when the story was at its simplest. When it was speaking of “a pane of ice, thumb thick”, or “watching as the flour and water performed their small alchemy”, or “listening to her breathing, which seemed the best sound ever made.” It is in these moments that The Way Past Winter shines.

The Way Past Winter is simple, evocative, and captivating. Its pacy adventure and flashes of rich imagination will appeal to fans of Katherine Rundell’s The Wolf Wilder and Abi Elphinstone’s Sky Song. One of Kiran Millwood Hargrave’s best books yet.

Author(s): Hilary McKay

Author(s): Hilary McKay

Author(s): Katherine Rundell

Author(s): Katherine Rundell

Author(s): Piers Torday

Author(s): Piers Torday

Author(s): Catherine Doyle

Author(s): Catherine Doyle

Author(s): Vashti Hardy

Author(s): Vashti Hardy

Rooftoppers by Katherine Rundell

Rooftoppers by Katherine Rundell

The Island at the End of Everything by Kiran Millwood Hargrave

The Island at the End of Everything by Kiran Millwood Hargrave

Today on the blog, I’m doing something a little different – a series review!

Today on the blog, I’m doing something a little different – a series review! Arsenic for Tea moves from Deepdean to the crumbling country pile of Fallingford (Daisy is, after all, the Honourable Daisy Wells, daughter of Lady Hastings and scatter-brained Lord Hastings). A compelling mystery ensues when a much-disliked guest at Daisy’s birthday party appears to have been poisoned. The confinement of the grand house is a standard mystery device; for Daisy, it raises the stakes of finding the culprit and highlights some already tricky Wells relationships. The tumbledown grandeur of Fallingford makes for a terrific backdrop (there’s something of the Old Professor’s House to it, maybe a whiff of P.G. Wodehouse’s Blandings or Dodie Smith’s I Capture The Castle, though thankfully not too much of Shirley Jackson’s We Have Always Lived In The Castle). While Hazel also comes from a wealthy background in Hong Kong, she’s a relative outsider to the idiosyncratic customs of England’s upper classes, which occasionally provides a dose of more dispassionate observation. Notable inclusions: Bertie’s Pre-Hipster Ukulele-Playing, Lord Hastings’ terrific “Daughter! Daughter’s friend!” line, and Uncle Felix generally.

Arsenic for Tea moves from Deepdean to the crumbling country pile of Fallingford (Daisy is, after all, the Honourable Daisy Wells, daughter of Lady Hastings and scatter-brained Lord Hastings). A compelling mystery ensues when a much-disliked guest at Daisy’s birthday party appears to have been poisoned. The confinement of the grand house is a standard mystery device; for Daisy, it raises the stakes of finding the culprit and highlights some already tricky Wells relationships. The tumbledown grandeur of Fallingford makes for a terrific backdrop (there’s something of the Old Professor’s House to it, maybe a whiff of P.G. Wodehouse’s Blandings or Dodie Smith’s I Capture The Castle, though thankfully not too much of Shirley Jackson’s We Have Always Lived In The Castle). While Hazel also comes from a wealthy background in Hong Kong, she’s a relative outsider to the idiosyncratic customs of England’s upper classes, which occasionally provides a dose of more dispassionate observation. Notable inclusions: Bertie’s Pre-Hipster Ukulele-Playing, Lord Hastings’ terrific “Daughter! Daughter’s friend!” line, and Uncle Felix generally. First Class Murder is Stevens’ homage to Agatha Christie’s Murder On The Orient Express. When a bloodcurdling scream leads to the discovery of a murdered passenger and a missing ruby necklace, Daisy and Hazel are faced with their first locked-door mystery. Despite a promise to give up sleuthing, Hazel and Daisy can’t help but try to crack a case when they see one. True to form, all the adult passengers – including a magician, a spiritualist, an heiress and more – seem to have secrets (and a reason to try to obstruct meddling teenagers, some more sourly than others). The Orient Express is described in suitably plush detail and noteworthy newcomers are to be found in fellow teenage detective Alexander and super-cool Miss Livedon (who also appears in a very spoilerific manner in the previous book). Three books in, Stevens’ prose is still engaging. I leave here an image of Kenneth Branagh’s mustache in the upcoming remake of the Christie original so it may be seared into your eyes:

First Class Murder is Stevens’ homage to Agatha Christie’s Murder On The Orient Express. When a bloodcurdling scream leads to the discovery of a murdered passenger and a missing ruby necklace, Daisy and Hazel are faced with their first locked-door mystery. Despite a promise to give up sleuthing, Hazel and Daisy can’t help but try to crack a case when they see one. True to form, all the adult passengers – including a magician, a spiritualist, an heiress and more – seem to have secrets (and a reason to try to obstruct meddling teenagers, some more sourly than others). The Orient Express is described in suitably plush detail and noteworthy newcomers are to be found in fellow teenage detective Alexander and super-cool Miss Livedon (who also appears in a very spoilerific manner in the previous book). Three books in, Stevens’ prose is still engaging. I leave here an image of Kenneth Branagh’s mustache in the upcoming remake of the Christie original so it may be seared into your eyes:

Jolly Foul Play sees Daisy and Hazel return to Deepdean, and at this point it must seem like trouble is following them around like a particularly dogged haunting, for lo and behold, there’s another murder. Now fourth formers and up against a horrid new batch of Big Girls, this is the most challenging book for Daisy and Hazel’s relationship. Hazel is becoming more self-confident, whereas Daisy has always been the dynamo; by book four, you’re really sensing that they need to check the imbalance. We get to see them navigate more of their friendships with Alexander and with fellow boarders Kitty, Lavinia and Beanie (and her outrageous climactic villain-wrangling). If I had to pick a least favourite of the books, it would probably be this one (I want Daisy and Hazel to be happy! I’d like to see them solving more non-fatal crimes!), but they’re all pretty solid and Stevens continues to twine themes with clue-solving. The series’ covers are so striking too, especially side-by-side.

Jolly Foul Play sees Daisy and Hazel return to Deepdean, and at this point it must seem like trouble is following them around like a particularly dogged haunting, for lo and behold, there’s another murder. Now fourth formers and up against a horrid new batch of Big Girls, this is the most challenging book for Daisy and Hazel’s relationship. Hazel is becoming more self-confident, whereas Daisy has always been the dynamo; by book four, you’re really sensing that they need to check the imbalance. We get to see them navigate more of their friendships with Alexander and with fellow boarders Kitty, Lavinia and Beanie (and her outrageous climactic villain-wrangling). If I had to pick a least favourite of the books, it would probably be this one (I want Daisy and Hazel to be happy! I’d like to see them solving more non-fatal crimes!), but they’re all pretty solid and Stevens continues to twine themes with clue-solving. The series’ covers are so striking too, especially side-by-side. I’m beginning to think setting really is right up there in Stevens’ forte, because the wintry Cambridge of Mistletoe and Murder is amazing. There are so many delectable details: the old buildings, the Chelsea buns, the secret society of rooftop climbers (reminiscent of Katherine Rundell’s Rooftoppers). The mystery is a real corker, with not one but two linked crimes and a plethora of suspects, and it was here that I really noticed how much Stevens’ prose and skill have improved; I would’ve liked a tiny bit more humour but there’s a level of mastery of her form here. She notes the disparity between the extravagant men’s colleges and the underfunded women’s colleges, and illustrates how much harder the fictional Amanda has to work than any of the male students, including Bertie, just to be accepted. Hazel’s growing sense of identity (“It really is not rude to exist, whatever anyone else says”) is touched upon when she meets students Alfred Cheng and George and Harold Mukherjee. Hazel has some romantic inklings in the book (she, like Daisy, is now almost fifteen) but Stevens foregrounds plot. I am also a decided fan of Aunt Eustacia. This one is pacy, fantastically twisty and really keeps you guessing.

I’m beginning to think setting really is right up there in Stevens’ forte, because the wintry Cambridge of Mistletoe and Murder is amazing. There are so many delectable details: the old buildings, the Chelsea buns, the secret society of rooftop climbers (reminiscent of Katherine Rundell’s Rooftoppers). The mystery is a real corker, with not one but two linked crimes and a plethora of suspects, and it was here that I really noticed how much Stevens’ prose and skill have improved; I would’ve liked a tiny bit more humour but there’s a level of mastery of her form here. She notes the disparity between the extravagant men’s colleges and the underfunded women’s colleges, and illustrates how much harder the fictional Amanda has to work than any of the male students, including Bertie, just to be accepted. Hazel’s growing sense of identity (“It really is not rude to exist, whatever anyone else says”) is touched upon when she meets students Alfred Cheng and George and Harold Mukherjee. Hazel has some romantic inklings in the book (she, like Daisy, is now almost fifteen) but Stevens foregrounds plot. I am also a decided fan of Aunt Eustacia. This one is pacy, fantastically twisty and really keeps you guessing.

Author(s): Jessica Townsend

Author(s): Jessica Townsend